Theft and Found

MiM Gallery is pleased to present “Theft & Found,” a group exhibition featuring work by Jacinto Astiazarán, Artemisa Clark, Alyse Emdur, John Finneran, Kari Gatzke, Aaron Gilbert, Arshia Fatima Haq, Fumi Ishino, Sarah Johnson, Khalif Kelly, Noé Olivas, Semco Salehi, Christine Wang, and Didier William, curated by artist Patrick McElnea.

In June 2020 the activist group Les Marrons Unis Dignes et Courageux staged a special kind of procession at the Musée du Quai Branly – Jacques Chirac, an ethnographic museum in Paris that owns over seventy thousand objects taken from sub-Saharan Africa. A thirty-minute long YouTube video shows the group’s leader Mwazulu Diyabanza removing a 19th century funerary pole of the Bari people (in today’s South Sudan) from a museum display to parade it through artifact-filled rooms. Though reported as a robbery by the international press, the video clearly documents that the activists make no attempt to rush or hide their actions. When they encounter a museum guard, they continue unfazed. Yet, promptly leveling theft charges, the French Ministry of Culture accused the group of “instrumentalization of heritage for political purposes.” A telling conflation in thiscontext. For as on-going debates on the restitution of colonial contraband let on, the “theft” of astolen object exposes the relations of property under racial capitalism as themselves forms ofexpropriation. If colonialism is theft of the first order, political change could require us, as Marquis Bey writes, “to steal on the second order, to steal back and let free what is unownable.”

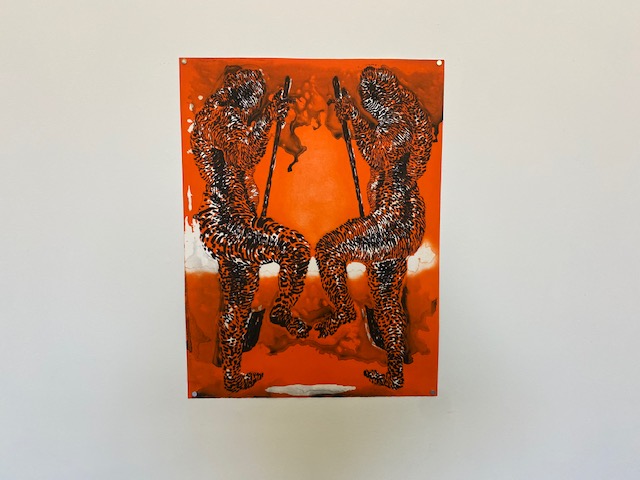

The artworks featured in “Theft & Found” explore the possibilities of thievery and reclamation, of the history of appropriation, excision, and remixing of symbols, of art’s uneasy relationship with property and propriety, and of the practices of copying that invent new lines of descent. Together they reflect on display practices and their relation to marked/unmarked modes of existence and on the heists that turn some objects into “art.” If artworks always pilfer from the repertoire of past works, from pop and trash, politics and philosophy, they do so roughly in the same way in which Jean-Paul Sartre writes about the child thief Jean Genet: He steals because he seeks to “dematerialize” reality, feeding his imagination on little bits of the real. Thus, in a society defined by the “ethics of ownership,” stealing becomes an “imaginary experiment in appropriation.” In other words, the one who has nothing silently declares her claim to everything. In this spirit, the artists featured in “Theft & Found” depart from “clean” conceptual practices toward a more embodied form of meditation on the circuits of reference that frame strategies of remembrance, appropriation, and reimagination.

Stealing back means to defy and confuse the rules of originality. It means using languages of abstract painting to mark stolen geographies, or banking on Trojan horses and stowaways to smuggle something past authenticity’s watchful gaze.“Theft & Found” mines the multiformpotentialities of thievery beyond institutional strategies of robbery-as-preservation/ preservation-as-robbery: From recombining images to restitute forgotten texts with a future to the echoes of fraud and impersonation in Internet culture, from shifting identities and deliberate source-derivative confusion, and from capitalist scarcity to imaginative abundance, “[i]n the ‘land of Chimeras,’ a conversion of signs is sufficient to change penury into wealth” (Sartre).